Do great artists need to be geniuses like Mozart, composing symphonies from age five? Or troubled souls, like Vincent Van Gogh, who cut off his ear before ultimately committing suicide? Are stable, hardworking artists, ordinary in every way but their artistic abilities, equally capable of producing masterpieces?

The connection between genius and artistry, on one hand, and mental demons or atypical personalities, on the other, has more than anecdotal evidence. On a modest level, the creative process is associated with breaking from convention, and atypical backgrounds such as living abroad are speculated to aid in its workings. Studies have also found higher incidences of mental illness among creative professions or geniuses.

That said, researchers debate whether such problems inform the creative process or are unfortunate side effects of creative capabilities or sensitivities. Other critics disagree entirely, discovering comparable rates of mental illness among the creative class and general population.

The research of Wijnand A. P. van Tilburg and Eric Igou, however, suggests that the troubled or aberrant artist stereotype is well established among the public. And that we hold the art of eccentrics in higher regard as a result.

——-

Igou and van Tilburg, researchers at the University of Limerick and University of Southampton, respectively, investigated how individuals’ perceptions of artists impact judgments of their art in the recently published paper “From Van Gogh to Lady Gaga: Artist eccentricity increases perceived artistic skill and art appreciation.”

Their work draws on the studies and popular perception cited above. In the same way that research has shown that people rate rap songs as better if they believe the rapper is black rather than white, they speculated that individuals will appraise art more positively if they believe the artist to be eccentric. In other, more ironic words, people think better of artists that conform to the stereotype of artists as unconventional.

In five experiments with university students, the researchers found the stereotype in action. In one, students liked Van Gogh’s painting Sunflowers better when told that the artist cut off his ear than those not primed with the information. In a second, students looked at paintings after reading a short bio of the fictional artist. The students who read a biography that included a description of the artist as “very eccentric” again rated the artwork higher.

To ensure that the students liked the paintings better because of the artists’ supposed eccentricity — and not because the group told about the artists’ idiosyncrasies received more information than the control group — a third study swapped the biographies with pictures. Students looked at the same paintings used in study 2, but the paintings were accompanied by a picture of a man with short hair in a white shirt, or a man “who was skinny, had half-long hair combed over one side of his head, had not shaved for several days, and was wearing a black shirt and vest.” Stereotypes triumphed again as the average looking artist received more lackluster reviews.

But do people expect eccentricity from all artists? What about a painter of conventional portraits? Or a designer working on Microsoft Office?

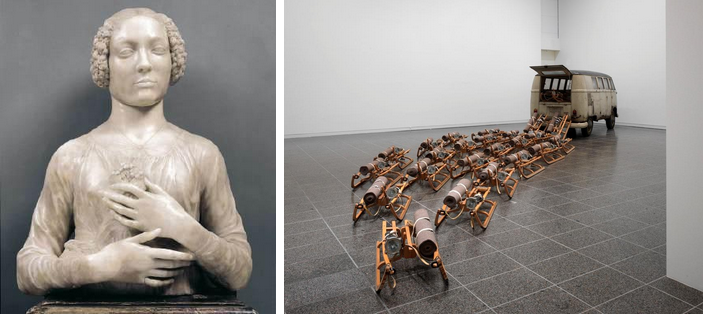

“Lady with a Bunch of Flowers” by Andrea del Verrocchio and “The Pack” by Joseph Beuys

Igou’s and van Tilburg’s fourth experiment asked students to rate the attractiveness of the two artworks shown above. The setup described the creator of each as a “respected contributor to art.” But some students additionally read about each artist that he was “eccentric.” When viewing the conceptual art (The Pack), the students once again rated the artwork higher when told of the artist’s eccentricity. But when evaluating the 15th century bust, the stated eccentricity of the artist had no impact on evaluations of the work.

The eccentric artist stereotype is a marketing staple. This author, for one, has often wondered how much of an artist’s eccentric image is the artist playing the part. In a final study entitled “Lady Gaga’s Tight Black Outfit,” the researchers tested whether people punish artists whose eccentricity seems inauthentic.

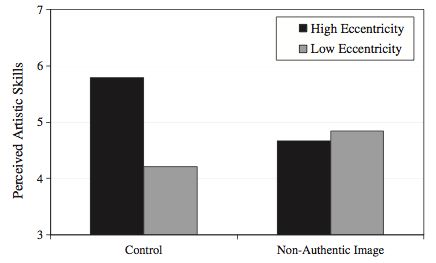

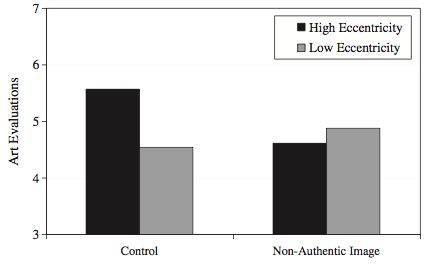

Students assembled by Igou and van Tilburg for the experiment all knew Lady Gaga’s music. So, they simply presented the participants with a short bio of Lady Gaga — who once accepted a video music award in a dress made of meat — accompanied by a picture of the artist. Half saw Gaga wearing “a tight black suit, black boots, black gloves, and a large, shiny mask”; the others saw a picture of her seated in a simple black dress with her hair in a ponytail.

The researchers then primed half the students in each group to doubt Lady Gaga’s genuineness by including a line in her biography that read “Some music critics say that the appearance and image of Lady Gaga is one of the most heavily marketed and strategically thought-through in contemporary pop-music.”

Reminding students of Lady Gaga’s eccentricity increased the ratings of her artistic skill and their appreciation of her music. But the picture had no effect on students primed to think that Gaga’s eccentricity may be a marketing ploy. People often turn to stereotypes as a quick way to understand the world. Since great artists tend to be eccentric (or so people believe at least), then people assume an eccentric artist is likely a great one. Artists can take advantage of the stereotype, but only if they’re not caught in the act.

——-

Museum-goers could preserve the sanctity of enjoying art by avoiding artists’ bios. But the eccentric artist stereotype is far from the only influence on our judgements.

In their paper, Igou and van Tilburg take pains to show that the effect they describe is distinct from those of construal level theory. The theory describes how greater distance — either literal or figurative — makes people think about objects and events more abstractly. For example, in one study, participants asked to describe themselves reading a science fiction book tomorrow described concrete details like “turning the pages.” Those asked to think about reading the book a year from now related more abstract descriptions like “broadening [their] horizons.”

In 2008, researchers investigated whether manipulating this tendency to think either more concretely or more abstractly could impact people’s appreciation of (more concrete) traditional art and (more abstract) contemporary art. In a similar setup, they recruited university students to look at artworks ranging from abstract or unconventional to more traditional.

“Apollo & Daphne” by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and “Brillo Boxes” by Andy Warhol

During a 50 minute period spent performing tasks otherwise unrelated to the experiment, the researchers asked students to either imagine their life a year from the present — or tomorrow. The participants then spent several minutes writing and reflecting.

Rather than ask students to rate how much they liked the art, the question of whether they would accept more contemporary pieces as art at all interested the researchers. So, they asked the participants to rank (from 1 to 7) each artwork’s fit within the category of “art.” Sure enough, those primed to think about the future accepted abstract works as art more readily.

——-

The researchers doubt that they would find the same effect among professional art critics, and the same could be true of van Tilburg’s and Igou’s study on artist eccentricity. Critics trained to focus on composition and style likely would not fall for the heuristic of whether artists seem too normal.

But at least for novices, studies like these provide an interesting lesson to consider while strolling through a museum: The context surrounding our perceptions and judgments of art may be as interesting as the artwork itself.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus.